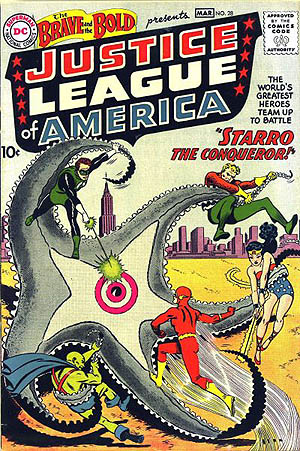

As I’ve mentioned in an earlier post, DC Comics has taken some ideas from its rival, Marvel Comics, when it came to enhancing the quality of their brand–in this case, incorporating all of their heroes into one shared universe.

But as you can see in the latest from the Washington Post, Marvel isn’t above swiping a good idea when it sees one, either:

That’s right — T’Challa of Wakanda will be the Black Panther no more, with an unknown woman taking his place as his country’s sacred protector. While details are scarce, writer Reginald Hudlin and Marvel EIC Joe Quesada seem enthusiastic about the series’ direction. “Our characters reflect the real world,” Quesada told WashPost. “To me, he’s the leader of the pack when it comes to that sort of stuff.”

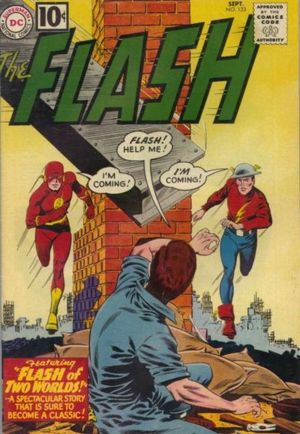

Yet this is far from the first time that Marvel has introduced a legacy hero to its ranks. In comic geekspeak, a legacy hero is typically an associate, lover, or sidekick of a popular hero who assumes the hero’s mantle if they fall in battle. DC, with it’s dramatic reimagining of its lineup, has long had legacy heroes, beginning with Barry Allen in 1961. This, however, cuts both ways: while some can argue Marvel trumps DC with a user-friendly universe, others can argue legacy heroes give a franchise prestige by adding a generational tone to it.

Perhaps the first legacy hero of the Marvel Universe would be Johnny Storm, the Human Torch. One of Marvel’s first heroes (he shares that distinction with Namor, the Sub-Mariner), the Human Torch was such a dramatic visual that Stan Lee reimagined the character as a member of the Fantastic Four. Of course, while his looks were identical to his Golden Age predecessor, Storm had an enormous ego that set him apart. However, because there was no connection given to the original, android Human Torch, the legacy hero aspect of the character was lost. Indeed, when the android returned from the grave, the conflict came within the pages of West Coast Avengers, where the team thought he was the forebearer of the android known as The Vision.

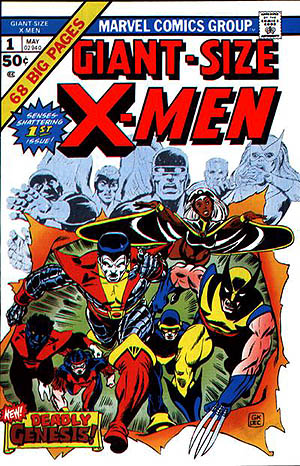

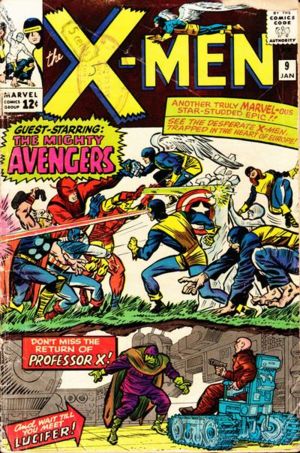

One of the main reasons for legacy heroes is not only to give a launchpad for a brand new design or powerset, but also to replace aging heroes with a set of relatable younger ones. (DC did this successfully with the replacement of Green Lantern Hal Jordan and Green Arrow Oliver Queen with twenty-something protagonists Kyle Rayner and Connor Hawke.) Furthermore, legacy heroes can branch off into their own deep mythologies, such as DC’s Teen Titans and Outsiders franchises. In a team setting, Marvel managed to emulate this with the X-Men, replacing the stodgy original X-Men with the All-New, All-Different X-Men (which introduced Wolverine, Storm, Colossus, and Nightcrawler to the masses). With the idea of “there must always be a team of X-Men,” the X-Men had finally struck gold, with its next spin-off, The New Mutants, gaining incredible popularity as it eventually grew into the mutant strike team X-Force.

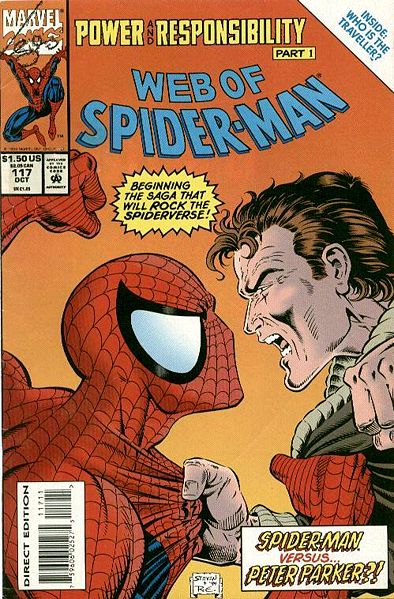

However, its attempts to do this on an individual scale resulted in disastrous consequences. In response to DC’s high-selling story arcs “The Death of Superman” and “Knightfall,” Marvel wanted to do something similarly controversial with Spider-Man. Furthermore, since the character had been married to his sweetheart Mary-Jane Watson in 1987, Marvel editors were concerned about the character’s apparent age, and how a married hero would resonate with young readers. The Clone Saga was born.

Spider vs. Spider: Web of Spider-Man #117 (Oct. 1994) kicked off a web of confusion and spectacle that nearly tanked a franchise.

To explain the Clone Saga is to delve into the murkier waters of Spider-Man lore. In 1973, writer Gerry Conway killed off Peter’s then-girlfriend, Gwen Stacy, having her neck broken as Peter Parker tried to catch her from a fall off the Brooklyn Bridge. However, Peter wasn’t the only one to mourn her: their biology professor, Miles Warren, was so wracked with grief he adopted a villainous persona known as the Jackal, and created a clone of the winsome Ms. Stacy. But the Jackal would not stop there–he also created a clone of Parker himself. The problem? Neither Spider-Man knew which one was the original. Conway wiggled his way out of this corner by killing one of them off, with the surviving Parker (and the reader) assuming he was real.

In 1994, however, Marvel brought the spectre of doubt back in a story arc that lasted nearly half a decade. By this time, Peter had suffered a nervous breakdown when his Aunt May had suffered a stroke and fallen into a coma. Hearing the news, Peter isn’t the only one to visit her–his clone had returned after five years on the road, now calling himself Ben Reilly. The doubt sparked conflict, and this conflict sparked sales.

However, soon thereafter, Marvel’s stock plummeted, and Editor-in-Chief Tom DeFalco was replaced by five editors. Frantic for ideas to keep the cash cow milking, the editors extended the Clone Saga to epic lengths, delving into minutia such as the method of cloning or whether or not both Peter and Ben (now called the Scarlet Spider) were clones. Nearly three years later, the bombshell was finally dropped: Peter Parker, the hero readers had kept up with since 1962, was the clone, and Ben Reilly was the real one. Fan outcry was so fierce that despite a short stint of Ben taking Peter’s place with a new Spider-Man costume, Ben was killed off by a resurrected Norman Osborn, and Peter was put back into the spotlight as the one, true Spider-Man.

For years after that, the idea of legacy heroes at Marvel was avoided, with new imprints (such as Heroes Reborn and the Ultimate line) filling that need with varying levels of success. Three writers in particular, however, have bucked Marvel’s previous batting average with the legacy hero: Allan Heinberg, Ed Brubaker and Matt Fraction. Heinberg, then the white-hot writer behind The O.C., headed the book Young Avengers in 2004, which spun off of the Avengers: Disassembled by introducing younger incarnations of classic Avengers known as Patriot, Hulkling, Asgardian, Iron Lad, and Hawkeye (based on Captain America, Hulk, Thor, Iron Man, and the recently-deceased Hawkeye), Heinberg was able to establish the Avengers as an ideal. Yet Heinberg did not completely embrace the legacy hero ideal, as the Young Avengers had their own internal struggles, including what to do when their founding member Iron Lad is actually a younger version of the time-travelling villain Kang the Conquerer, whose absence from evil would actually destroy the world. Despite Heinberg’s delayed scheduling–indeed, following issue #12, there hasn’t been another regular series with the characters, and the writer would later go on to do the same with Wonder Woman–sales showed that the legacy hero, when done right, could succeed at Marvel.

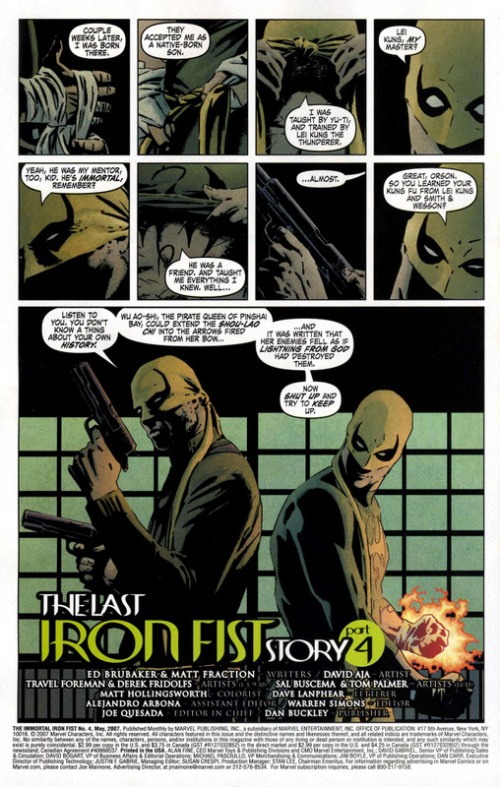

Meanwhile, Brubaker and Fraction, in their run of the Immortal Iron Fist, established a retroactive legacy for the Iron Fist mythos by creating Orson Randall, an Iron Fist who left the shining city of K’un L’un after World War I. The series was a complete success, and gave the main protagonist, Danny Rand, a new direction as well as a broader array of powers.

Brubaker continued the legacy hero tradition in his run of Captain America, which made national headlines for killing off its title character during the fallout of the summer blockbuster Civil War. Yet Brubaker had a plan–Cap’s one-time sidekick Bucky Barnes, recently resurrected as the murderous Winter Soldier during the beginning of Brubaker’s run, was tapped as the new Captain America, who would battle his own inner demons and doubt while trying to rout a conspiracy from Steve Rogers’ archnemesis, the Red Skull.

Indeed, with Heinberg, Brubaker, and Fraction’s contributions, Marvel’s legacy heroes are now in plentiful supply. The only question is: can Hudlin manage to A) give the original character a meaningful exit, and B) give this newcomer a three-dimensional and, most importantly, sympathetic take? Only time will tell.